A Library of Indigenous Knowledge of Place

from top left: Beaded Wedding Bag, Gleason Family, Print of “Gramma, how do I learn?” Rose Imai Taken by Bears, Dempsey Bob,

little girl: Ellie Madril

Ancestor Mask, Tim Paul, Model for Ten Elders Poles, Tim Paul

Bear Basket, Isabel Rorick, Robin Rorick,

Woman sitting: Rose Imai

The Indigenous peoples or First Nations of the Northwest, particularly in British Columbia are renowned for their epic wood sculpture and carvings, notably their totem poles. This artistic tradition can be traced to their ancient ways of transmitting their genealogies, cultural knowledge and native science. When a group of Northwest Coast Artist / Knowledge Holders were presented with the opportunity to join the Native American Academy’s project to create a Sculpture Garden devoted to the study of Native Science, they did not hesitate.

The formation of a carving team is altogether an interesting story. Originally, it was master carver Joe Martin who was tapped to lead, then Martin recommended his relative, Nuu-chal-nuth knowledge holder and artist Tim Paul as lead carver. Tim in turn invited other renowned sculptors, carvers and educators to attend the initial presentation to meet representatives from The Native American Academy. Robin Rorick, Chuutsqua Rorick, Charles Elliott and Dempsey Bob, internationally known Tahltan/Tlingit artist and teacher all joined the project. Further meetings resulted in the artists mapping out notions and ideas for their designs and for the education elements.

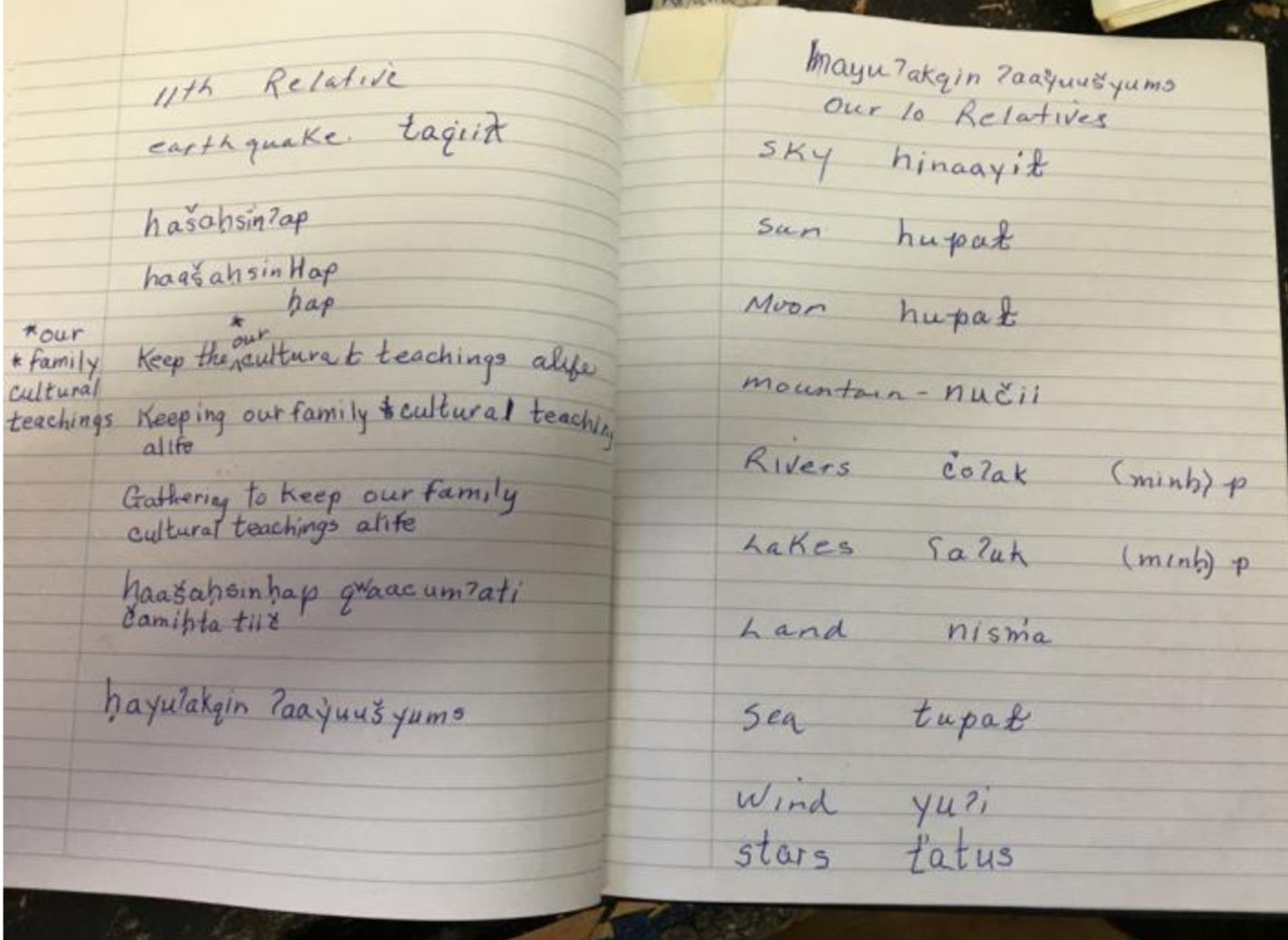

The first work done in Port Alberni, British Columbia were of two small models of the Hesquiat teaching of the Ten Elders, which speaks of the Hesquiat relationship to Nature and names the ten relatives. Initial public documentation of the project came in an article published in Langscape Magazine, followed by a video overview of the project which was produced in partnership with The Cultural Conservancy. Community engagement was through a series of meetings with members of the San Francisco Arts Commission, Native California tribal leaders and the Port Alberni Carving Team in Victoria, B.C. Other artists and knowledge holders, including language experts from the Nuu-chal-nuth, Tahltan/Tlingit, Haida Gwai’i, nations conferred about language revitalization and educational focus.

A collaborative partnership was formalized with The Cultural Conservancy joining the project. Fully integrating their support was the International Funders of Indigenous Peoples who hosted a community meeting in San Francisco to introduce the Sculpture Garden to a regional community of funders. Local tribal leaders attended meetings with interest, enthusiasm, and a desire to participate. The indigenous youth who have a penchant for modern technologies, their imaginations triggered by the possibilities, eagerly began envisioning their contribution to the project and educating the public about their culture.

According to the implementors, “The entire project is an organic process. The creation of a Sculpture Garden of Native Science and Learning as a library of Indigenous knowledge of place, is more than an objective goal, it is an ongoing shift in consciousness from thinking that the science of measurement, numbers, machines and instruments is the only trustworthy way to know the world to the understanding that the bodies of knowledge held by Indigenous peoples is scientific knowledge, its study and practice requires precision and rigor. Its processes are deductive, experimental, pragmatic, coherent and relevant. And, the critical differences: that Native Science is holistic, focused on interdependencies, harmony and balance and includes meaning, purpose, and social implications makes it a powerful context and provides a values matrix for linear, fragmented western thought. To continue to imagine that Native people have no knowledge of Mathematics, physics, astronomy, chemistry, or to accept the unexamined assumption that there is only one way to know the world becomes life threatening as the Earth shifts to restore herself. “ It is important that the Sculpture Gardens are understood as invaluable places for the study of native science.

Despite periodic bouts of uncertainty in funds, the project is achieving its goals. The project holders comment: “Fortunately, indigenous peoples are resourceful and generous and accustomed to working with limited funds.”

The participation of women cannot be understated as the knowledge is incomplete without them. Traditionally, among the British Columbian tribes, women weave their knowledge in baskets, hats, shawls, dance curtains, etc., and a few women carve. The men are then given the woven piece to add their knowledge through painting, and this completes the whole.

All in all, the project remains rich in dynamic partnerships and consistent participation of the youth, elders, women and persons with disabilities. New leaders are emerging through consistent engagement and community ownership is evident in their sustained support of the project. Documentation (photography, film, video and podcast) and social media networking are bringing young Native IT specialists and modern technologies into the project.

Knowledge systems are integral in the project such as food production/preservation; sustainable resource management; handicraft development as part of cultural heritage, distinct patterns and symbols, and revitalization of indigenous language.

Those currently involved in the Sculpture Garden of Native Science and Learning: the Tuscarora, Anishinabe, Yaqui, Mi’kmaq, Nuu-chal-nuth, Haida, Tahltan Tlingit, Blackfoot, Chickasaw, Tewa, Ohlone, Pomo, Mewuk, Lakota, nations see this first garden as a model for a network of libraries across North America, and a learning process for all those involved, as they bring the knowledge and ways of life of their ancestors into the 21st century.

The project “The Sculpture Garden of Native Science and Learning” was implemented in December 2017 by The Native American Academy with support from PAWANKA Fund.

for further information: vnthater@berkeley.edu, www.silverbuffalo.org melissa@nativeland.org