The Borana pastoralist people of Northern Kenya had been observing how climate change impacts on their communities with the gradual erosion of traditional coping practices. Women used to churn milk to make ghee during the rainy season in preparation for drought. Milk made into yoghurt and preserved lasted for half a year. When drought came, village elders ordered the slaughter of healthy animals for meat preservation that lasted for a year. In recent times, their food system has been commercialized and the concept of relief food has replaced communal slaughtering, meat preserving and sharing with donors’ and government’s intervention in food distribution processes. Milk is sold now in towns to travellers instead of being churned into ghee. Relief foods and cash transfer schemes are prevalent.

The dwindling number of Elders, astrologists, entrail readers and local historians who provide accounts of social, political and environmental occurrences over the years is alarming. Astrologist Galgalo Jidha rues that he might not be needed to be consulted anymore because he does not have accurate predictions due to the impacts of climate change. This sentiment was shared by 92-year-old Elema Duko who lost 84 heads of cattle after a long drought that wasn’t expected nor foreseen.

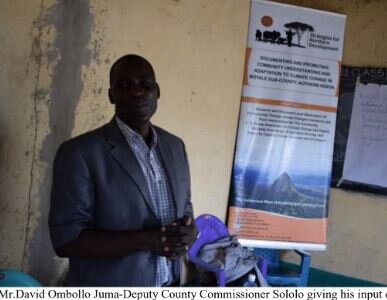

In this light, the Strategies for Northern Development (SND) initiated a project that responded to this downtrend and revealed the potentials of a community to reclaim their practices of adaptation to changing times. They recovered past stories on climate, weather, and survival, and together with community members of Moyale sub-county, involved resource persons, particularly the village elders, culture bearers, and authorities from scientific agencies to put together a comprehensive picture and plan of how traditional practices past and present, science, and indigenous knowledge can mitigate the harsh consequences of climate change, and help communities adapt and recover.

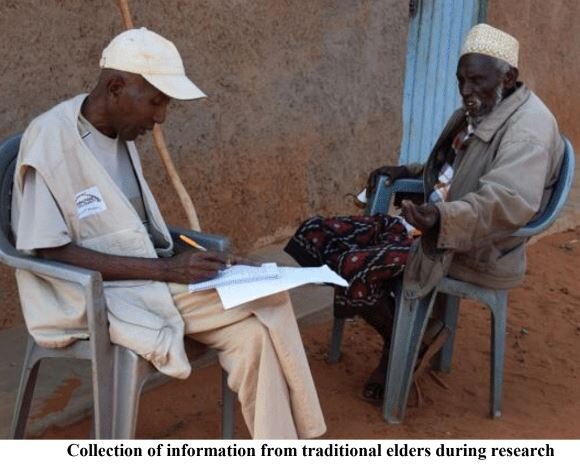

Indigenous youth documented local climate change related issues such as drought and rainfall patterns, and their effects on traditional ceremonies. Through interviews and FGDs, they recorded the knowledge of diviners, traditional spiritual leaders and local historians in remote areas and the challenges they faced with recurrent drought that killed their animals offered for the ceremonies. The works of traditional entrails readers, those who count days, and astrologists were documented and their views and recommendations incorporated in the reports.

Fairs were held to promote, share, and transmit knowledge and experiences between generations and communities. This enabled the communities to utilize available scientific and traditional information related to climate change and the corresponding sustainable strategies.

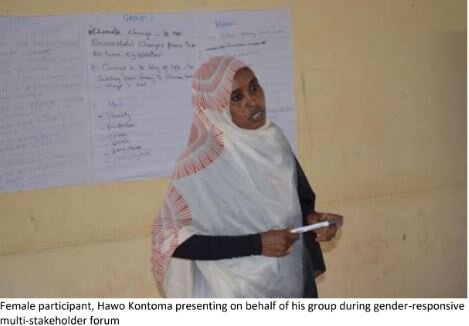

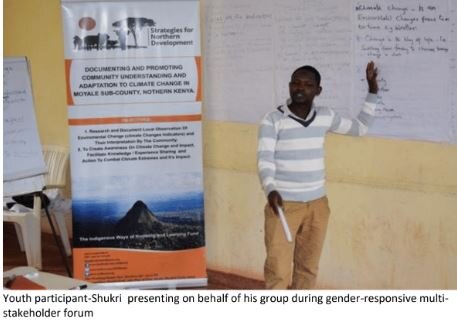

Additionally, fora on peace, culture and environment gathered various ethnic and tribal youth organizations in Moyale. The local communities, particularly the women, became more aware and capable of taking appropriate actions against the impacts of climate change through facilitation of gender-responsive and inclusive forum and workshops which were venues to amplify marginalized voices and focus on gender issues in relation to climate change impacts. Key issues discussed were experiences and lessons from other areas, gender and gender mainstreaming, gender and UN declaration on the rights of indigenous people, and gender sensitive and mitigating strategies.

Awareness, engagements and interactions were further generated through community radio programmes that had wide reach, local community meetings, performance of traditional songs, storytelling sessions led by elders, spiritual gatherings and religious leaders’ forums, naming and other religious ceremonies, and popularization of riddles. These were effective and interesting avenues in stirring interest and insights, appreciation, and conversations on the impacts of climate change and corresponding coping or adaptation strategies. Sufficient documentation of all the project activities highlighted indigenous knowledge that will reinforce the Borana peoples’ resilience in the face of intensifying threats of climate change.

The project has enhanced and expanded the knowledge of beneficiaries and their communities. The SND was instrumental in giving way to new strategies, innovations and practices that communities themselves developed to face head on the climate-induced challenges to their traditional practices of monitoring the environment and their livelihood. Specifically the research component made this possible, incorporating the perspective and views of local communities and inputs from indigenous and academic institutions regarding contemporary knowledge on environment and climate.

The research findings will definitely contribute to the communities’ crafting of new strategies and practices for them to cope with climate-induced challenges. The trainings and action plans will guide future direction of the local community in monitoring and mitigating the adverse impacts of climate change.

Those who read the past can clearly read a promising future of Moyale, with the youth actively leading the efforts to carry on the tradition of the Borana pastoralist people in safeguarding their communities and resources.