The Nuba people in Sudan inhabit the Nuba Mountains which have been ravaged with war and political issues in recent times. Against this backdrop, the Delibaya Nuba Women Development Organization (DNWDO) initiated a project to ensure the retention of their language that would be passed on to future generations. Their main mode of learning is oral tradition and their language is gradually being lost due to urban migration and education. While the women transmit and teach the language (hence “mother tongue”) to the children, the community elders are the custodians of the language and cultural heritage. Children and youth sit around and listen to the elders’ stories said in mother tongue, learning about the tribe’s history, rites of passage, ceremonies, and other important lessons. “Our elders used to read and write but when we learned (the language), we did not learn how to read and write it, we only spoke it. When we moved to the city, we did not teach our children to even speak it,” Salwa Yunis noted.

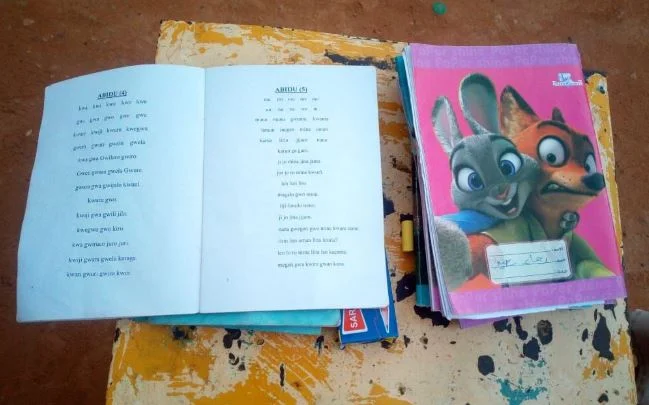

In the early 90s, a community elder wrote a book on the Nuba language and the local church facilitated its publication. The book was a written record of the language and a learning tool for grammar which was threatened with loss if nothing was done to revitalize it.

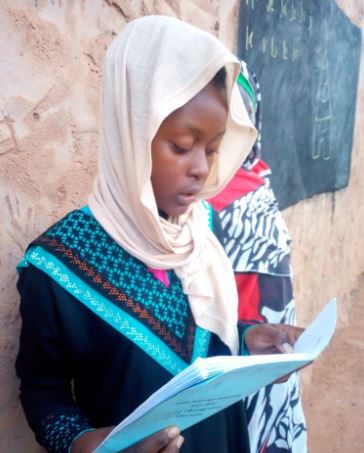

The DNWDO formed a language committee and with teachers, discussed about enhancing and revising the curriculum, teaching methods, and revising the language book. An editing committee was tasked to edit and report back to the language committee on changes that had been made. Subsequently, the printed text books were used in language classes where the indigenous language was taught to community members. They learned the alphabet, reading, writing, and vocabulary. “The written language is important because this way we’re sure it can last for a long time. This program not only revives but also revitalizes our language,” Ismael Kenani said.

Besides the language classes, traditional cultural dances were taught, practiced and showcased during the National Nuba Indigenous Festival in late December 2018. As part of the traditional outfit, both simple and complex beadworks embellished the dancers who performed traditional cultural dances and songs. The language and the traditional dance classes were an inter-generational platform where the youth interacted with the elders. The youth asked questions to which the elders shared their knowledge, experiences, and stories about traditional territories and cultural practices that are both no longer observed and those that are still practiced.

“We are so grateful to have this language and cultural revitalization program. Previously, only a few people were interested in learning, but now interest is increasing. I myself am part of the classes so that I can read and write my language better,” Shamsum Kome, the Chair of the Language committee declared.

An exclusive elders’ class was held for the community elders who requested to learn to read and write the language which they only knew how to speak fluently. Elder Abdulnabi Kuku said, ”Before this, I can only speak my language, but now I am able to read and write it. This makes me very proud.” This was a special class because they were not only elders, but holders of a wealth of knowledge about the people’s past and present vital in determining the tribe’s future.

Story time gathered community members for conversations about the past and the present. This was the younger generation’s opportunity to ask questions in an informal setup and appreciate the changes from the past to the present. “Our children are lost because they do not know their roots and this is our own fault. But when they learn our language, they are able to find themselves and learn about our ways and culture,” language teacher Surutia Kachu observed.

The committee and the teachers devised more creative ways to ensure better attendance and practice of the language. Mixed classes with the elders encouraged the youth to learn and practice conversations or pronunciation with the elders when at home and in their neighborhood. “Things are changing now and we are all learning together and this makes me happy. I hope we can continue until everyone learns,” Salwa Yunis shared.

The DNWDO intends to further strengthen their organization and their partnership with the community as they to seek other partners to support the program and the publication of a dictionary which is important in the community’s preservation of their language and cultural heritage.

The pride among the Nuba people is palpable as they reclaim their identity through their language. “Community members are writing their names in our language and calling each other with our traditional names. It’s amazing that we can now confidently write our own names in our language and do so proudly,” Kabashi Rahma enthused.

Mary Kuku, DNWDO Director summed it up: “During the war, our language played a big role in keeping us safe. Our language is our secret and our peace. This program is important especially because we are in a country that has discriminated against us. It is our responsibility to ensure that we continue to jealously protect our language and culture for ourselves and the future generations.”

The project “Nguro Ebang (I am Heiban)” was implemented by the Delibaya Nuba Women’s Development Organization in Sudan, Africa for the Nuba Peoples with support from PAWANKA Fund in December 2018.